A Talk with Bill Gates: On Innovation, Sacrifice, and What Really Matters

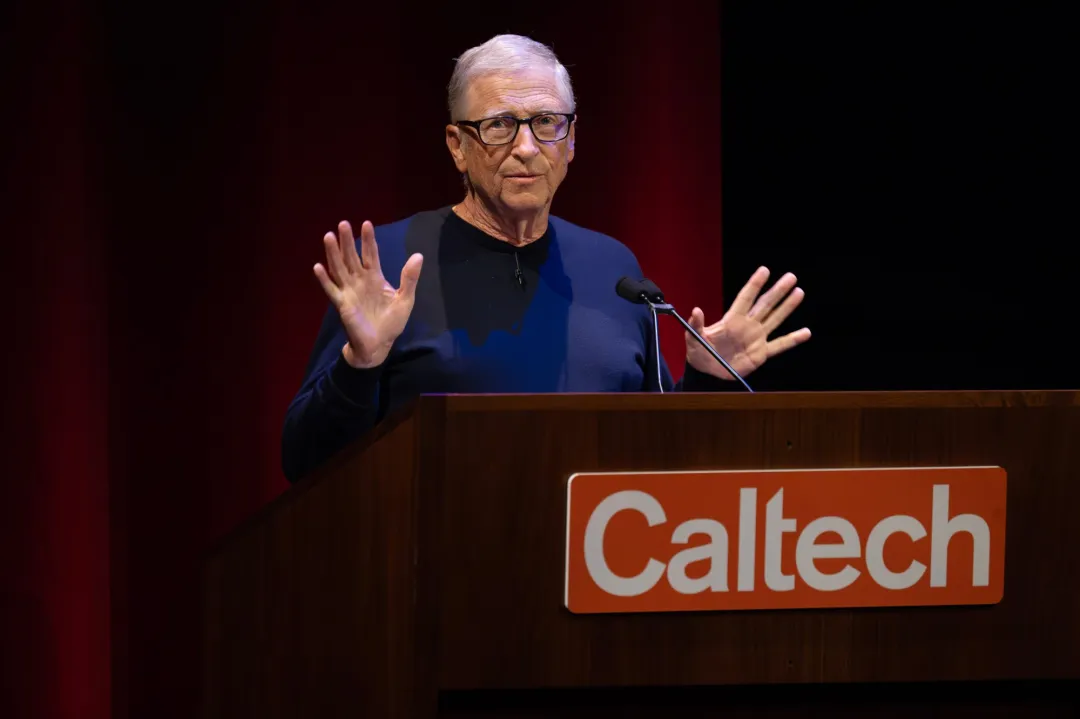

I sat in Beckman Auditorium last night, November 3rd, my iPad open, my pen ready. Around me, students whispered excitedly. Faculty members settled into their seats. The air felt heavy with anticipation—that particular Caltech energy when something important is about to happen.

Bill Gates was coming.

I had been looking forward to this for weeks. Not because I’m obsessed with billionaires or tech giants, but because I wanted to gain a deeper understanding. I wanted to hear someone who has spent billions on climate and global health (source) explain how we’re supposed to balance it all. How we’re supposed to save the world when we can barely save ourselves.

The lights dimmed. Applause filled the auditorium.

And then he walked on stage.

The Beaver Engineer

He started with a joke about beavers. Our mascot. I smiled—genuinely smiled, which felt rare lately. He explained that beavers are engineers, climate engineers, building dams that store carbon and filter water. “That’s fitting,” he said, “because a lot of the work all of you do will help with the challenges we face with climate.”

I looked around. All of us. He meant me, too.

Even though some days I can barely understand my physics problem sets. Even though I spend nights in Kerckhoff—the same building where Dulbecco once worked in a sub-basement—wondering if I belong here at all.

But Gates kept talking, and I kept listening.

The Truth About Climate

Then he said something that made the room shift. Something I wasn’t expecting.

“There are some people who say that climate change is an existential or almost world-ending threat,” he began. I could feel people leaning forward. “Fortunately, although climate’s an extremely serious problem, it’s not of that nature. It will not end civilization.”

I heard murmurs. Confusion. Maybe disagreement.

But he didn’t back down. He explained that while climate change is extremely serious, it won’t destroy humanity. It will make parts of Earth difficult to live in. It will threaten human welfare. But it’s not, in most locations, the biggest threat to the human condition.

And then he said the thing that’s been echoing in my head ever since:

“My lens here, and I suggest it should be the lens broadly, is while we reduce temperature increase as much as we can, the real measure is all the things we’re doing to help the most vulnerable people on the planet.”

Human welfare.

Not just temperature targets. Not just emissions. But lives. Actual lives.

I wrote that down. Underlined it twice.

Ten Years of Progress (That Nobody Talks About)

Gates reminded us that it’s been exactly a decade since the Paris Climate Agreement. Ten years since he launched Breakthrough Energy. And in that time, something remarkable happened.

“A decade ago, if emissions had continued unabated, we were on track for warming above 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century,” he said. “Now, projected emissions say we’re looking at more in the range of 2 to 3 degrees instead of four or even five.”

Wait. What?

We cut projected emissions by 40 percent in ten years?

I didn’t know that. Nobody talks about that. All we hear is doom, disaster, the world is ending, we’re all going to die. But Gates stood there and told us: innovation worked. It’s working. Electric vehicles now make up one in four cars sold. Solar and wind costs have plummeted. Battery prices dropped by over 90 percent.

The Green Premium—the extra cost of being clean—has reached zero for some technologies. And when that happens, markets take over. Progress accelerates.

“I’m quite optimistic,” he said.

I wasn’t sure I’d ever heard someone talk about climate that way. With hope. With data. With proof that humans can actually solve problems.

Breakthrough Energy: 150 Companies Building the Future

He walked us through Breakthrough Energy’s portfolio—now comprising over 150 companies, working across all five major emission sectors. Electricity. Manufacturing. Agriculture. Transportation. Buildings.

Some of the innovations sounded like science fiction:

- Next-generation nuclear fission reactors for reliable clean power

- Vaccines that prevent cows from burping methane (yes, really)

- New methods of making steel with zero emissions

- Windows that cut building energy use by over 30 percent

- Space-based solar power

That last one made me sit up. Gates said he met with Caltech’s team today—the one working on the solar space-based power demonstrator. He admitted he thought it was science fiction. But after meeting them, he said, “It sounds like they are right on track, which would be a fantastic contribution.”

I study in Kerckhoff. I walk past those labs. And suddenly I realized: I’m surrounded by people building the future. Right here. Right now.

Maybe even me.

The Part Nobody Wants to Hear

But then Gates shifted. His voice got quieter, more serious.

He discussed the other aspect of his work: global health. The Gates Foundation. Vaccines. Malaria. HIV. Child survival.

And he told us something heartbreaking.

“This will be the first year that childhood deaths goes up in a long time.”

Up. Not down. After decades of progress—cutting childhood deaths in half since 2000—they’re going up again.

Why?

Because aid budgets are being cut. Rich countries spend less than 1% of their budgets helping poor countries, and that number is dropping. Money for childhood vaccines? Down dramatically. Malaria bed nets? Down. HIV medicines? Down.

“Those things will result in millions of deaths,” Gates said, “until we can get them reversed.”

I thought about my own struggles. My exhaustion. The nights I can’t sleep. The pressure. The fear of failing.

And then I thought about a child in Nigeria who might not get a vaccine because funding was cut.

Perspective is a strange, uncomfortable thing.

The Trade-Offs We Shouldn’t Have To Make

Gates explained that with limited resources labeled for helping poor countries, we’re forced to make impossible trade-offs. Climate adaptation versus vaccines. Solar panels versus malaria nets.

“To be clear,” he said, “we’re having to take very limited resources and make trade-offs that we shouldn’t have to.”

His memo—the one that went viral last week, the one everyone has been arguing about—was intended to explain this. He wasn’t saying climate doesn’t matter. He was saying: with the money we have, how do we save the most lives?

And the answer surprised me.

Prosperity IS Adaptation

The University of Chicago’s Climate Impact Lab ran a study. They asked: what happens to climate-related deaths if poor countries experience economic growth?

The deaths drop by more than 50 percent.

Prosperity itself is climate adaptation. When people have money, they can afford air conditioning during heat waves. Better housing during storms. More resilient food systems during droughts.

“Deaths from weather disasters go down dramatically as countries get better off,” Gates explained. “The economic cost becomes completely absorbable.”

So the question isn’t just: how do we stop climate change?

It’s: how do we help people survive climate change while we’re working on stopping it?

And the answer, Gates argued, is agriculture, health, and energy.

Seeds That Save Lives

Gates talked about agriculture with the same passion I heard when he discussed semiconductors or AI. Most of the world’s poorest people are subsistence farmers—working on two to four acres, earning about $2 a day, with no safety net. A single drought or flood wipes them out for an entire season.

But innovation is changing that.

In Nigeria, drought-resistant maize varieties are boosting output by over 50 percent. That’s enough to feed a family for a year and still have crops left to sell—five months’ worth of income.

In India, AI-powered text messages warning farmers about monsoon timing saved a million acres of crops last year. And Caltech researchers helped make those predictions.

Caltech. Us. This place.

“Our goal,” Gates said, “is to have the advice for the poorest farmer in the world better than the advice that the richest farmer has today.”

Artificial intelligence. Not for chatbots or generating papers. But for helping a farmer in sub-Saharan Africa know when to plant. What seeds to use. How to deal with plant diseases.

That’s what innovation should do.

The Conversation: Defending Nuance in a Polarized World

After his talk, Gates sat down with Amy Harder from Axios. She asked about his memo—the one that sparked global controversy.

“Who here has read all 17 pages?” she asked the audience.

Some hands went up. Not many.

I had read it. All of it. Because I wanted to understand.

The criticism came from all sides. Climate activists said he was backing away from climate action. Climate deniers claimed he was admitting they were right. President Trump even posted about it, declaring victory.

Gates looked exhausted for a moment. Then he responded:

“A gigantic misreading of the memo.”

He explained—slowly, carefully, as if he were teaching—that his funding for mitigation is increasing. His funding for adaptation is going up. His funding for global health is going up.

He has $200 billion. That’s what he’s committing over the next 20 years to these three causes. And it’s not enough. It will never be enough.

“I’m going to run out of money in 20 years,” he said matter-of-factly.

Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe suggested framing climate not as its own “bucket” but as a hole in all other buckets—affecting hunger, disease, malnutrition.

Gates pushed back.

“If you can’t map to dollars per ton avoided, then what is it? Religion?” His voice was sharp. “This is a numeric game in a world with very finite resources.”

And I understood. He wasn’t being cold. He was being honest. When you have limited money and unlimited suffering, you can’t just say “everything matters equally.” You have to calculate. Measure. Decide.

It’s brutal. But it’s necessary.

The Question About Geoengineering

Someone asked about geoengineering—technologies that could temporarily adjust global temperatures by putting particles in the atmosphere.

Gates admitted he’s funded research on it. Not because he wants to use it. However, if we reach a tipping point—if positive feedback loops start accelerating warming beyond our control—we need to know if we have options.

“You have to have a principle of extreme caution about using those things,” he said.

But knowledge matters. Understanding matters. Even of scary things.

I thought about my own fears. The ones I carry. The ones that wake me at 3 a.m.

Sometimes you need to study the thing you’re afraid of. Not to use it. But to know.

The Challenge to Us

Gates ended by speaking directly to us. The students. The researchers. The future.

“This campus has an extraordinary track record—Nobel laureates, NASA missions, breakthroughs that reshape entire fields,” he said. “I challenge you to think broadly about what we need to get done. How we direct our innovation, given the values we have and the priorities we have.”

Then he said something I’ll remember for a long time:

“I’m a climate activist, but I’m also a child survival activist. And I hope you will be too. That’s the best way to make sure that everyone gets a chance to live a healthy life, no matter where they’re born or what climate they’re born into.”

He paused.

“We know the challenges—make clean everything cheaper, make farmers more resilient, keep people healthy, help educate people. We don’t yet know who will invent the solutions, but I bet some of you are sitting in this room.”

The applause was long. Standing ovation. I stood too, my notebook pressed against my chest.

What I’m Still Thinking About

Walking back to my dorm, the night air cool against my face, I kept replaying his words.

We don’t yet know who will invent the solutions, but I bet some of you are sitting in this room.

I think about my own failures. The times I’ve fallen—literally, in the sand with my horse, and metaphorically, in classes that broke me. The times I pushed too hard and broke myself.

But Gates didn’t just talk about success. He talked about trade-offs. About limited resources. About making impossible choices.

He emphasized the importance of doing what you can with what you have.

And maybe that’s the lesson. Not perfection. Not doing everything. But doing something. Measuring impact. Choosing carefully. Working on problems that matter.

There are 150 Breakthrough Energy companies. But there could be 1,500. Or 15,000.

There are Caltech researchers predicting monsoons and developing drought-resistant crops. But there could be more.

There are people like Renato Dulbecco—my inspiration, my predecessor—who came from Italy after the war, who worked in a sub-basement at Kerckhoff, and invented methods that changed biology forever.

And maybe, just maybe, some of us in that auditorium will do something that matters too.

Not because we’re geniuses. Not because we’re perfect. But because we’re here. Because we have the tools. Because someone like Bill Gates stood on that stage and told us: you can do this.

We have to do this.

What Human Welfare Really Means

The thing I keep coming back to is this: Gates never separated climate from humanity. He never said “choose one or the other.” He said: measure everything by how it affects lives.

Lives.

Not emissions targets. Not temperature goals. Not abstract numbers on a graph.

Actual human beings. Children who might not get vaccines. Farmers whose crops might fail. Families displaced by floods.

And I think about my own life. The pressure I put on myself. The way I measure my worth by grades, achievements, whether I’m “enough.”

But what if the measure isn’t perfection? What if it’s just: did I help? Did I make something better? Did I use my resources—limited as they are—to reduce suffering?

Maybe that’s what we’re supposed to do here. Not save the entire world alone. Not solve everything. But find one problem, one innovation, one life we can improve.

And then do it.

Hic et Nunc

Live in the present. Here and now.

That’s what I tell myself when the panic sets in. When the deadlines pile up. When I can’t breathe.

But last night, listening to Bill Gates, I realized “here and now” doesn’t just mean surviving my own life. It means recognizing that right now, somewhere, a child is dying of malaria. Right now, a farmer is watching their crops fail. Right now, the climate is changing.

And right now, in labs and classrooms across this campus, people are working on solutions.

I’m not sure if I’ll be one of them. I’m unsure whether I’ll invent the next breakthrough or just scrape by with passing grades.

But I was in that room. I heard him speak. I took notes. I understood.

And perhaps that’s enough to get started.

Thank you, Dr. Gates. Thank you, Caltech. Thank you to everyone working on problems bigger than themselves.

I’ll do my best to make you proud.

Camilla