Italian Heritage Month: Between Memory, Identity, and the Legacy of Renato Dulbecco

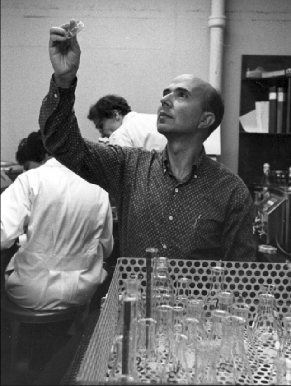

Renato Dulbecco in a Caltech lab, December 1961. (Photo: James McClanhan)

One of the articles I have been featured in stated that the future Dulbecco is Camilla Fezzi, who is flying to Caltech, where he was. At that time, I did not know precisely who he was…I am honest, but today, after a year and numerous books, I really want to dedicate this article to one of my fonts of inspiration. As I lean over my desk, slumped biology books, scratched calculations, and lecture notes that seem to multiply as quickly as the viruses Renato Dulbecco once studied, I sometimes feel that strange conflict: the will to belong in this rarefied, demanding space and the tug of another, deeper heritage that lives in the folds of memory and blood. Being Italian at Caltech, surrounded by ambition and innovation, is both grounding and disorienting. I carry a history of voices, songs, and scars that belong to an old Europe—one of family kitchens filled with garlic and dialect, of resilience through centuries of political chaos and improvisation. However, I also occupy a lab, a library, and a classroom where the language is not Italian, but universal: mathematics, physics, and biology.

This month, Italian Heritage Month in the United States, prompts me to consider not just where I am, but also why. What does it mean to be Italian here, among chalkboards, DNA sequences, and Nobel medals? What truths can we find about our place in American life, not only as descendants of workers and sailors but as thinkers? The history of Italians in America is complex: it is hardship, insult, and labor—but also resilience, artistry, and discovery. And if there is one figure whose life embodies the arc from struggle to illumination, from Italian soil to American triumph, it is Renato Dulbecco.

Dulbecco’s story—recorded in his 1998 oral history at Caltech—is not simply a chronology of dates and discoveries. It is a mirror. In him, I see traces of myself: the stubborn boy tinkering with seismographs at age twelve, the weary student standing at a crossroad between medicine and physics, the quiet immigrant in an attic laboratory at Indiana University struggling with English but determined to decipher the hidden code of life. Reading his words, I feel the pulse of both Italy and America, intertwined, shaping not only his identity but the shape of modern biomedical science itself.

Italy in America: From Prejudice to Persistence

To understand the power of Dulbecco’s achievements, I must step back into the broader story of Italians in the U.S. For most Americans, the image of the Italian immigrant conjures up old photographs: men in flat caps, women with shawls over their heads, and children selling newspapers in congested city blocks. Between the 1880s and World War I, millions of Italians—especially from the depressed south—crossed the Atlantic. They arrived broke, often illiterate, and were met with suspicion. “Dago,” “wop,” “greaseball”—the language was violent, the stereotypes unforgiving. Italians were accused of criminality, anarchism, and backwardness; even their Catholic faith inspired fear in a Protestant-majority nation.

In New Orleans in 1891, eleven Italians were lynched in one of the largest mass executions in U.S. history. In cities like Boston and New York, Italians packed into insalubrious tenements, laying bricks, digging subway tunnels, and cleaning sewers. They were needed for labor but rarely welcomed into the American imagination as equals.

Yet despite prejudice, Italians carved spaces for themselves. Children’s accents softened; education opened doors; traditions—food, music, holidays—persisted. Out of this slow survival emerged a cultural influence that reshaped entire cities. And here lies the dual nature of being Italian in America: initially stigmatized as alien and dangerous, Italians eventually became artists, politicians, athletes, and intellectuals whose excellence could no longer be ignored. Italian Heritage Month exists today not just to romanticize pasta and opera, but to remind America how far Italians had to walk to belong and how much they gave along the way.

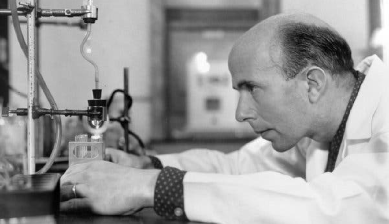

(Credit: Denise Gellene)

Renato Dulbecco: The Italian Spirit Amplified in Exile

Dulbecco, however, was not part of that early peasant wave. His journey unfolded later, after World War II, in the intellectual migration of European scientists to America. Yet in a deeper sense, he shared the same spirit of adaptation.

His oral history reveals the arc vividly: born in Porto Maurizio in 1914, his father’s engineering influenced him to calculate and construct, while his mother instilled in him a passion for medicine. By sixteen, he had earned his diploma from a liceo classico, and by twenty-two, he held an M.D. Already, his instinct was to invent: he built radios, a seismograph, even a heart-measuring apparatus in medical school. For him, experimentation was not confined to professional labs—it was a personal habit.

But at the same time, fascism breathed down his young life. At university, he studied under Giuseppe Levi, alongside Rita Levi-Montalcini—another future Nobel laureate. Levi, a passionate anti-fascist, agonized over the regime’s demands on intellectual allegiance. Mussolini’s racial laws of 1938 soon expelled Jewish professors, including Levi, while forcing Levi-Montalcini into hiding. Dulbecco, meanwhile, was sent as a physician to the Russian front with Mussolini’s army. In the midst of that frozen catastrophe, he witnessed annihilation. In his testimony, he recalls arriving at a station in occupied Poland and realizing for the first time, with horror, that Jews were being marked simply “kaput” after forced labor—that death awaited them (Cohen, 1998, pp. 8–9). That moment—his “turning point”—was when his loyalty turned firmly against fascism.

Back in Italy, he refused to rejoin the army. Instead, he became a doctor to partisans in the mountains near Torino, patching wounds, improvising dentistry, cycling to Turin for medical supplies while hiding from authorities, even sleeping above a morgue after Allied bombings. This image—an Italian physician with a bicycle, navigating bombs and fascist patrols with quiet defiance—is perhaps the most Italian portrait of all: stubborn, scrappy, resilient.

(Credit: Indiana University)

It prepares us for his later reinvention in science. Time and again, Dulbecco embodied this trait Italians know so well: arrangiarsi—the art of making do, of bending circumstances into opportunity. First in war, then in science.

From Italy’s Ruins to Indiana’s Attic Labs

In postwar Torino, laboratories were rubble. Equipment was scarce, and scientific support was nonexistent. Yet Italy’s intellectual life had not died; it was searching for oxygen. In 1946, Dulbecco was visited by Luria, once his colleague at Levi’s laboratory. Luria had escaped to the United States and was working on phages at Indiana. Seeing Dulbecco’s talent and shared interest in genetics, he invited him across the ocean. By 1947, Dulbecco boarded a ship, leaving behind a secure appointment at the University of Turin to plunge into uncertainty in America.

He described his arrival in New York with humility: poor English, meager contacts, and nights spent in makeshift accommodations. At Indiana University, the laboratory space was primitive—an attic under the roof, just desks and a technician, until James Watson arrived to share the workspace. Yet out of this modest beginning, history turned. Dulbecco’s work on multiplicity reactivation—showing that viruses could recombine genetic material and recover viability after ultraviolet damage—was one of his first American contributions (Cohen, 1998, pp. 19–21).

Caltech and the Quiet Revolution in Animal Viruses

But it was at Caltech, beginning in 1949, that Dulbecco truly innovated. Invited by Delbrück, he moved west—a scientific gamble made with the same daring as his earlier partisan defiance. Initially still focused on bacteriophages, he soon pivoted when offered the chance to use Division funds earmarked for virus research. Rather than continue with bacteria, he invented methods to study animal viruses in a quantitative way.

At first, he was banished to a sub-basement laboratory in Kerckhoff…so exciting I am studying in the same building!!!!! . There, with just one research assistant, he developed the plaque assay for animal viruses by dispersing tissues with trypsin and creating uniform cell cultures. Suddenly, researchers could measure animal viruses with the same accuracy as phages.

From those tiny plaques grew major applications: assays for polio (essential to vaccine development), systems to study tumor viruses, and an entire generation of molecular virology methods. What Caltech gave him—a space of interdisciplinary dialogue, freedom from the rigid departmental structures he had known in Italy—he seized fully. When he showed Max Delbrück the first visible plaques in an animal virus culture, Delbrück recognized its importance immediately. It was 1952. Biology had turned a corner.

Integration, Cancer, and Nobel Recognition

In the following decade, Dulbecco pressed deeper, moving from polio to polyomavirus and Rous sarcoma virus. With students like Howard Temin and postdoctoral fellows like Harry Rubin, he investigated the viral induction of cancer. His crucial insight was almost poetic: just as immigrant identity can merge with that of the host nation, viral DNA could integrate into the host’s DNA. Cancer, he realized, stemmed not from transient infection but from a genetic marriage—permanent, transformative, dangerous.

This idea, now central to oncology, was initially speculative. He defended it through painstaking hybridization experiments, telegram-confirmed results, and collaborations. By the 1970s, the evidence was undeniable. In 1975, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, an honor that recognized the persistence of an Italian American immigrant who had helped redefine cancer as a genetic disease. Thank you, Dr. Dulbecco. I know you can hear me. I will do my best to make America and you proud.

Italian American Heritage Month, established in 1989, is celebrated around the country each October.

Being Italian at Caltech: My Reflections

When I read his oral history in my dorm room, with my lamp casting shadows over my textbooks, I feel suspended between two identities. There is the weary undergraduate grinding late into the night, sometimes uncertain, sometimes overwhelmed by equations and expectations. And then there is the other self: the Italian voice that whispers through celebration memories, through Catholic festivals, through my grandmother’s stories of survival.

This dualism—Italian and American, heritage and aspiration—is sometimes heavy, sometimes liberating. I wonder: did Dulbecco feel it too? He left Italy with its Fascist scars and intellectual poverty, yet carried Italy in his habits, in his willingness to improvise, to build from scraps, and to think not in straight lines but in leaps of creativity. This is the same for me. I wasn’t leaving anything behind in Italy; that is my past. It was high school, fear, and obsessions that are better forgotten.

To be Italian here, now, is not to live in exile, but in continuity with that same spirit: making space out of difficulty, shaping life from fragments. We Italians know both beauty and ruin, opera and rubble, pasta and politics. We bring that awareness to Caltech’s clean labs and ambitious syllabi. When I feel crushed under exams, I think: if Dulbecco could pedal through bombed-out Torino to buy dental supplies for partisans, I can pedal through a midterm week and keep a smile on my face!

Heritage as Horizon

Italian Heritage Month is not just an occasion for nostalgia or food fairs. It is an acknowledgement that immigration is never just about physical movement but about intellectual and cultural grafting. Italians did not only lay bricks and stir sauces—they stitched their improvisational genius into science, literature, and politics.

Renato Dulbecco’s life is the perfect emblem for this: a man who carried fascism’s scars but turned them into scientific courage; who embodied arrangiarsi in the lab as much as on the battlefield; who proved that Italians in America were not temporary laborers but permanent innovators.

As I sit here, my pen scratching across another page of notes, I remind myself that being Italian in America means belonging doubly: to the old resilience and to the new discoveries. Dulbecco’s legacy at Caltech assures me that this is our space, too. Italians have been here, shaping quietly, profoundly. And we, the new generation, carry that lineage. Out of hardship, creativity. Out of exile, discovery. Out of heritage, hope.