Democritus: The Atomic Visionary Whispering Through Caltech’s Labs

Democritus: The Ancient Greek Who Would Have Loved Caltech’s Labs (If He Had a Microscope)

Imagine if some guy from 2,300 years ago walked into a Caltech physics lab, took one look at an electron microscope, and said, “Yep, told you so.” That guy would be Democritus, the ancient Greek philosopher who somehow managed to predict the existence of atoms without a single piece of scientific equipment—just pure brainpower, a lot of thinking, and probably too much free time.

Sure, he didn’t get everything right (he thought atoms had little hooks to stick together, which is adorable but incorrect), but the sheer audacity of his ideas still resonates with modern science. If Democritus were alive today, he’d fit right in at Caltech—probably wandering around campus, laughing at his own jokes, and asking if he could borrow a supercomputer “just to check something.” But Democritus wasn’t just some guy who came up with atomic theory and called it a day. His philosophy extended far beyond tiny particles—he had an entire worldview built around rationality, curiosity, and the idea that the universe runs on natural laws rather than divine whims. In fact, Democritus had a way of looking at the world that feels strikingly modern, as if he were an ancient prototype of a Caltech scientist.

Democritus, laughing philosopher and forefather of atomic physics. Credit: vinap via Adobe Stock/Public Domain via Wikimedia.

Democritus: The Original Scientific Rebel

Democritus (c. 460–370 BCE), known as the “Laughing Philosopher” because he believed happiness was the key to a good life (and probably because he found the ignorance of others amusing), was a man ahead of his time. Unlike many of his philosophical peers, who were busy debating abstract concepts like “What is justice?” or “Does reality even exist?”, Democritus asked a much more practical question:

“What is everything made of?”

For Democritus, the answer wasn’t divine intervention, magic, or some mystical force—it was atoms and void. He proposed that the universe consists of tiny, indivisible particles (atomos, meaning “uncuttable”) that move through empty space (kenon, meaning “the void”). These atoms, he argued, are eternal, indestructible, and the fundamental building blocks of all matter.

This might sound obvious today, but at the time, this was a radical idea. Most people thought the universe was made of four elements—earth, water, air, and fire (thanks, Aristotle, for setting science back by centuries). Others believed reality was shaped by gods or supernatural forces. Democritus, however, insisted that everything—from stars to stones to human emotions—was the result of atomic interactions. To put it in modern terms, think of it like LEGO bricks. If you take a bunch of LEGO pieces, you can construct a spaceship, a castle, or an incredibly unstable tower that will absolutely collapse the second you show it to someone. The pieces themselves don’t change, but their arrangement does. That’s how Democritus saw atoms—unchanging, eternal, but capable of forming an infinite variety of things.

Now, keep in mind, this was before the periodic table, before chemistry, before anyone even knew what oxygen was. He was just making educated guesses based on pure reasoning. No lab, no experiments—just vibes.

Democritus vs. Aristotle: The Ultimate Philosophical Smackdown

If Democritus was the cool, forward-thinking scientist of his time, Aristotle was… well, the guy who ruined everything. Aristotle was super famous, which meant that when he disagreed with Democritus (which he did, loudly), people listened.

Aristotle preferred the idea that everything was made of four elements—earth, water, air, and fire—which, let’s be honest, sounds more like a rejected Avatar: The Last Airbender script than a scientific theory. He outright dismissed the idea of atoms, setting scientific progress back by about 2,000 years. Imagine if someone today said, “Nah, I don’t believe in quantum mechanics” and then convinced everyone else to stop researching it. That’s basically what happened to Democritus’s atomic theory.

But science, like a stubborn Caltech student who refuses to leave the library, always makes a comeback. Fast forward to the 19th and 20th centuries, and scientists like John Dalton, J.J. Thomson, and Ernest Rutherford started proving that atoms were real. By then, of course, Democritus had been dead for over two millennia, but we like to imagine him somewhere in the afterlife, smugly whispering, “Told you so.”

A Universe Without Gods? Scandalous!

Democritus’s theories didn’t just challenge early physics; they also clashed with religious and mystical beliefs. Many ancient Greeks believed the gods had a direct hand in shaping the world. But Democritus? He wasn’t buying it. According to him, the universe wasn’t created by divine beings—it simply existed, governed by natural laws. Atoms moved, collided, and combined according to necessity and chance, not the whims of Olympus. This idea, known as mechanistic determinism, was way ahead of its time. It foreshadowed the scientific principle that the universe follows consistent, predictable laws, a concept central to modern physics.

If Democritus had access to a physics lab, he’d probably be the guy constantly testing theories, trying to prove that things worked because of natural forces, not supernatural ones. He would have been all about data, equations, and experimental proof—in short, a perfect fit for Caltech.

The Laughing Philosopher: A Man Who Knew How to Have Fun

Now, you might be picturing Democritus as a super-serious, lab-coat-wearing, chalkboard-scribbling philosopher-scientist. But here’s the twist: Democritus was known as the “Laughing Philosopher” because he believed that happiness came from knowledge—and he found human ignorance downright hilarious.

He wasn’t laughing at people in a mean way—he just thought that understanding the universe should make people happy. He believed that fear and superstition came from not knowing how things worked, and that the best way to achieve peace of mind was through learning, rational thought, and scientific inquiry.

If he were at Caltech today, you’d probably find him:

- Laughing at how people still believe in astrology.

- Debating quantum mechanics with undergrads over coffee.

- Making bad physics puns in the middle of problem sets at 3 AM.

- Writing a paper on how the multiverse theory aligns with atomic determinism.

- Arguing that happiness is directly proportional to scientific knowledge.

In other words, he’d fit right in.

Democritus, painting by Dosso and Battista Dossi, 1540. Credit: public domain.

Democritus’s Boldest Idea: Everything Is Just Atoms in Motion

At the heart of Democritus’s philosophy was a simple but mind-blowing idea:

Everything in existence—planets, plants, people, thoughts, emotions—is just atoms moving around in different ways.

This means that even things like love, music, and consciousness had to be explained in physical terms. He believed that sensations and thoughts weren’t mystical forces but rather the result of atomic interactions in the body. This idea is eerily close to modern neuroscience and physics. Today, we know that emotions come from biochemical signals in the brain, that consciousness arises from neural activity, and that even the most complex phenomena can ultimately be broken down into interactions of fundamental particles. If Democritus could see the research happening at Caltech today—from quantum mechanics to AI-driven neuroscience—he’d probably be thrilled (and maybe a little smug). After all, he basically called it 2,000 years in advance.

Democritus’ Radical Theory of Perception: Seeing Is Believing (Sort Of)

Okay, so Democritus didn’t just believe that atoms made up everything—he also had some pretty wild ideas about how we actually perceive the world. Forget fancy neuroscience; for Democritus, all perception boiled down to atoms literally smacking into us.

His idea went something like this:

- Every object in the world is constantly shedding thin layers of atoms called eidôla (think of it like atomic dandruff, but way more scientific).

- These layers float through the air like tiny, invisible film projections, shrinking and expanding as they travel.

- Only the layers that shrink enough can squeeze into our eyes, where they physically impact our sense organs, enabling us to see.

- The further these atomic films travel, the more they get distorted—kind of like how a Snapchat filter makes your face look weird if the Wi-Fi is bad.

Now, if this sounds bizarre, consider this: he was trying to explain how vision worked without knowing anything about photons, optics, or neural processing. Given those limitations, his theory is actually kind of impressive. But he didn’t stop at sight—every sense, he argued, worked through direct atomic contact. Taste? Different shapes of atoms bumping against your tongue. Sound? Atoms crashing into your eardrum. Smell? Atoms sneaking up your nose. Of course, not everyone was convinced. Theophrastus, Aristotle’s student, pointed out a major issue: if atoms always cause the same sensations, then why does honey taste sweet to some people but bitter to others? Democritus had an answer for that too—he argued that:

- Honey isn’t perfectly pure—it contains a mix of different atoms, and while sweet atoms are dominant, bitter ones might be lurking in there too.

- Your body has to be in the right condition to perceive things correctly. If you’re sick, your sense organs might be out of whack, making you more sensitive to certain atoms.

In other words, Democritus was unknowingly laying the groundwork for the idea that perception is influenced by both external reality and internal conditions—something modern neuroscience fully supports.

Why Does the Ocean Change Color? Democritus Had a (Weird) Answer

One of the most mind-bending parts of Democritus’ perception theory was his take on color. Unlike most people, who assume things look blue because they are blue, Democritus argued that colors aren’t real properties of objects—they’re just how we perceive different atomic arrangements. He thought color changed based on atomic position—so when you see the sea turn from deep blue to foamy white, it’s not because the water itself is changing color, but because the arrangement of atoms is shifting, altering how the light films (eidôla) reach your eyes. Aristotle, ever the critic, found this idea ridiculous, but Lucretius (a later Roman poet-philosopher) backed it up, noting that if atoms themselves were actually blue, the ocean wouldn’t be able to change color at all. This was a wildly ahead-of-its-time concept—essentially an early version of the idea that color is a perceptual phenomenon, not an intrinsic property of matter. Today, we know color is determined by how surfaces absorb and reflect light waves, which isn’t too far off from what Democritus was suggesting, just without the atomic films.

Democritus’ Theory of the Soul: Fire Atoms and the Meaning of Life

Now, if you thought Democritus’ physics were weird, wait until you hear about his theory of the soul. Unlike most ancient Greeks, who believed in an immortal soul that lived on after death, Democritus took a fully materialist approach. He believed that the soul (psychê) was made of fire atoms—tiny, ultra-mobile particles that gave living beings their ability to move, think, and function. Why fire atoms? Because fire is always moving, and Democritus figured that anything responsible for thought and action had to be constantly in motion. (If you’ve ever tried to keep up with a hyperactive physics major pulling an all-nighter, you get the idea.) But this also meant that when you die, your fire atoms scatter—and that’s it. No afterlife, no eternal soul, just atoms dispersing back into the void.

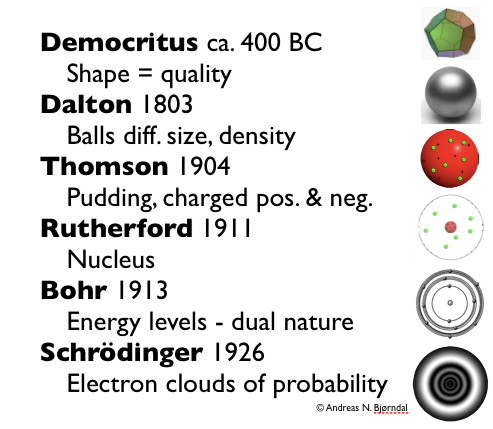

The evolution of our understanding of matter. Credit: Andreas N. Bjørndal.

This take didn’t sit well with a lot of people, but it was one of the earliest fully naturalistic explanations of life and consciousness. In a way, he anticipated modern neuroscience—suggesting that thought was purely physical, rather than the result of some mystical soul-stuff.

Democritus’ Take on Reproduction: Atomic Genetics Before It Was Cool

Democritus even had a theory of heredity, and while it wasn’t exactly Mendelian genetics, it was still surprisingly sophisticated. He believed that every part of the body contributes atoms to reproductive material, meaning that children inherit traits from both parents because both parents contribute atomic “seeds.” He even speculated that the dominance of certain atoms in the reproductive mixture determined whether a child was male or female. This was one of the earliest attempts to explain heredity through material causes, foreshadowing later ideas about genetic inheritance.

Democritus’ Theory of Knowledge: Can We Even Trust Our Senses?

Democritus had a bit of a dilemma. On one hand, he believed that all knowledge comes from our senses—after all, how else are we supposed to learn anything? On the other hand, our senses are kind of terrible. They distort reality, mislead us, and sometimes outright betray us (like when you see a mirage in the desert or when honey tastes bitter for no reason). His theory went something like this: thought and perception are both caused by tiny atomic images (eidôla) entering our bodies and reshaping our minds. But since these images can get distorted along the way—bouncing off other atoms, stretching, shrinking—the information we receive isn’t always reliable. Kind of like how a game of telephone always ends in disaster, except instead of kids whispering nonsense, it’s atoms colliding in the void. This led him to a deep philosophical crisis: if atoms are real but we can’t perceive them directly, how do we know anything at all? This is the kind of thing that keeps philosophers (and overworked grad students) up at night. Some later skeptics took advantage of this, arguing that if our senses constantly contradict each other, we might as well admit that we know nothing.

Democritus wasn’t having that. He admitted that our senses aren’t perfect, but they’re the best tools we’ve got. If the mind starts doubting them completely, it’s basically sawing off the branch it’s sitting on. So, he settled for a kind of “well, they’re good enough” epistemology—sure, our senses can deceive us, but with logic and careful reasoning, we can get closer to the truth.

He even extended this idea to the gods—arguing that our knowledge of divine beings comes from massive eidôla (giant atomic films) floating around in the air, giving us impressions of powerful beings. Some scholars think this was Democritus’ way of subtly roasting traditional religion, reducing divine visions to floating atomic residue. Others think he genuinely believed these eidôla were real beings, just not immortal ones. Either way, he was definitely not making friends with the priesthood.

Democritus vs. Infinite Divisibility: The First Physics Thought Experiment

If you’ve ever had a math teacher make you think about slicing a pizza infinitely many times until it just disappears into nothingness, congratulations—you’ve thought like an ancient Greek philosopher.

One of the biggest problems in early philosophy was Zeno’s paradoxes, which argued that if space and matter were infinitely divisible, then motion (and basically everything else) would be impossible. Democritus and his crew, not wanting to be stuck in a paradoxical nightmare, decided to solve this by inventing atoms—tiny, indivisible building blocks of reality. But what did they mean by “indivisible”? Was it a theoretical indivisibility (as in “we just can’t divide them anymore”)? Or a physical indivisibility (as in “these things are literally unbreakable”)? Scholars argue about this to this day, but one thing is clear: Democritus was not about to let reality dissolve into infinity.

He even had a fun little thought experiment to prove his point. Suppose you could divide something infinitely—what would you be left with? If you say “dust,” then congratulations, you haven’t actually divided it infinitely. If you say “nothing,” then oops—how did something come from nothing? Checkmate, infinite divisibility. He also posed a weird math problem about cones that basically boiled down to this: if slicing a cone at different heights gives you different-sized circles, then shouldn’t the cone have “steps” rather than a smooth surface? If not, then how do the slices magically change size? This problem haunted mathematicians for centuries until calculus came along and saved the day. But for the time, Democritus was basically just flexing his ability to break people’s brains with logic.

Democritus’ Ethics: The Laughing Philosopher’s Guide to Happiness

Democritus wasn’t just about atoms and void—he also had a lot to say about how to live a good life. And, in true Democritus style, his ethical philosophy was both deeply insightful and surprisingly fun. First off, he believed that happiness (or “cheerfulness,” as he called it) is the ultimate goal of life. But here’s the twist: happiness isn’t about money, power, or external stuff—it’s about your internal state of mind. (Basically, Democritus was the original “happiness comes from within” guy, long before self-help books made it cliché.)

He preached moderation, self-discipline, and not getting too attached to things you can’t control. He even compared taking care of your soul to medicine—just like a doctor treats the body, philosophy should treat the mind. (If he were alive today, he’d probably be a big fan of therapy.) One of his most radical ideas was that humans have the power to shape their own destiny. He didn’t believe in fate or divine intervention—just atoms bouncing around and people making choices. This was a pretty bold stance in a world where most people thought the gods controlled everything.

He also had some interesting thoughts on politics. Unlike some philosophers who saw society as an unnatural constraint, Democritus believed that humans naturally form communities. He thought laws were important, but only if they actually helped people live better lives—otherwise, they were just pointless rules made up by power-hungry people.

François-André Vincent’s Democritus among the Abderitans, completed in the late 18th century.

So, what’s the takeaway? Think rationally, live moderately, don’t obsess over things you can’t control, and try to enjoy life. Honestly, not bad advice for a guy who lived 2,300 years ago.

Why Democritus Would Have Loved Caltech

So, what does an ancient Greek philosopher have in common with a cutting-edge research institution like Caltech? More than you’d think.

1. He Was Obsessed with Finding the Fundamental Truths of the Universe

Democritus wanted to understand the smallest components of reality, just like Caltech physicists today study quarks, neutrinos, and other subatomic particles. If he had access to the Large Hadron Collider, he’d probably be first in line to smash some protons together just to see what happens.

2. He Believed in the Power of Logic and Reason (Even When Everyone Else Disagreed)

Caltech students know what it’s like to tackle impossibly hard problems, armed only with equations, a whiteboard, and an alarming amount of caffeine. Democritus did the same thing, except instead of problem sets, he used pure logic to figure out the fundamental nature of matter.

3. He Had a Great Sense of Humor, Which Is Essential for Surviving Science

If you’ve ever made a physics pun in the middle of a study session at 3 AM, you and Democritus would probably get along.

If Democritus were alive today, he’d probably be a Caltech physics major, hanging out at the Athenaeum, debating quantum theory with professors, and laughing at the absurdity of the universe. He’d be the one asking, “But what if we go even smaller?” every time someone explained particle physics. His story is a reminder that curiosity, logic, and a willingness to challenge conventional thinking can change the world—even if it takes 2,000 years for people to realize you were right. So the next time you’re struggling through a physics problem set, just remember: Democritus would have struggled too—except he wouldn’t have even had a calculator.