Aristotle: The Philosopher of Reason, Reality, and the Tangible World

And here we are at the last pillar of ancient philosophy, which, in some way, can also be defined as the father of the modern one. After our Platonic dive into the world of ideas, metaphysical realms, and abstract thought, it’s time to plant our feet firmly on the ground. If Plato was the dreamer with his head above the clouds, Aristotle is the realist with his hands in the soil. He’s the philosopher of practicality; the one who took the abstract musings of his teacher, Plato, and said, “Alright, but how does it really work?” A man of observation, experimentation, and logic. If Plato was the architect of the ideal world, Aristotle was the engineer of reality—the one who built the bridge between raw perception and reasoned understanding. And this cannot be more like the reality we live in every day here at Caltech, the concreteness of things, reason, rational and non-metaphysical analysis. Most of the time we ask ourselves why we must take exams in humanities or take courses in the sector, the answer lies in Aristotle who considered knowledge as something 360°, capable of shaping you completely.

Figure 1: Aristotle and the research of ευδαιμονια

So, let’s step out of the hyperuranion (thank goodness!) and delve into Aristotle’s world. A world that’s not just theoretical but also practical, observable, and—dare I say it—approachable.

Aristotle and Plato: A Philosophical “It’s Complicated”

Imagine this: Plato and Aristotle are sitting in a café in Athens (bear with me). Plato is passionately gesturing about his world of ideas, the abstract realm where concepts like justice, beauty, and goodness exist in their purest forms. Aristotle listens, nods politely, and then interrupts, “But Plato, my dear teacher, how do these ideas connect to the world we live in? Where’s the evidence?”

This is the core of their philosophical divergence. Plato believed in two worlds: the intelligible and the sensible. Aristotle, however, saw no need for a separate world of ideas. For him, the “idea” of a tree didn’t exist in some abstract hyperuranion—it existed in the tree itself. Form and matter were inseparable; the essence of a thing wasn’t floating in some metaphysical realm but was embedded in the thing itself. Where Plato was metaphysical, Aristotle was physical. Where Plato sought universals, Aristotle sought particulars. Where Plato gazed upwards, Aristotle looked around.

The Foundations of Aristotle’s Philosophy

Aristotle (Stagira, 384 BC – Euboea, 322 BC) was a polymath in the truest sense of the word. Philosophy, biology, physics, ethics, politics, logic, poetics—he didn’t dabble in these fields; he defined them. He believed that real knowledge was a mix of different realities, and the true instructor should be aware of all of them. If Plato was the father of metaphysics, Aristotle was the father of everything else.

His philosophy is grounded in empiricism—the belief that knowledge comes from sensory experience. Unlike Plato, who distrusted the senses and prioritized intellectual intuition, Aristotle argued that the senses are our starting point for understanding the world. You observe, you analyze, you reason, and you conclude. It’s a system that feels remarkably familiar to those of us in the scientific world.

Aristotle’s Four Causes

One of Aristotle’s most influential contributions is his doctrine of the four causes. He attempts to answer the fundamental question: Why do things exist the way they do?

Let’s take an example—a statue of Plato (because irony is fun).

- The Material Cause: What is it made of? Marble, in this case.

- The Formal Cause: What is its form or essence? The shape of Plato that the sculptor has carved.

- The Efficient Cause: Who or what made it? The sculptor.

- The Final Cause: What is its purpose? To honor Plato, or perhaps just to decorate a fancy Athenian courtyard.

Aristotle’s genius lies in the Final Cause, or what he calls telos, τελοσ (from Greek, end). Everything, according to Aristotle, has a purpose, an end goal. For Aristotle, understanding something’s purpose is key to understanding its very nature. It’s a beautifully holistic way of thinking—one that ties together material, form, and action into a unified explanation.

Hylomorphism: Matter and Form

If Aristotle’s philosophy had a tagline, it would be “Form and matter are one.” (Not as catchy as Nike’s “Just do it,” but still profound.)

For Aristotle, every physical object is a combination of matter (what it’s made of) and form (what makes it what it is). Take a chair, for instance. Its matter might be wood, but its form is what makes it a chair—its shape, its function, its essence. Without form, it’s just a pile of wood. Without matter, it’s…well, nothing.

This idea of hylomorphism (from the Greek ηυλε = matter, and μορϕε = form) is Aristotle’s way of bridging the gap between Plato’s dualism (the separation of the intelligible and sensible worlds) and the observable reality we live in. Form and matter aren’t separate—they’re intertwined.

Aristotle’s Ethics: The Search for the Good Life

If Plato’s ethics were about finding the ultimate, abstract “Good,” Aristotle’s ethics were about living the best possible life here and now. His approach is practical, and rooted in the realities of human existence. At the heart of his ethics is the concept of eudaimonia (from ancient Greek ευ: well/good and δαιμον: soul/the inner conscience), often translated as “happiness” but better understood as “flourishing” or “living well.” For Aristotle, the goal of human life is to achieve eudaimonia—a state of being where we fulfill our potential and live in harmony with our nature.

How do we achieve this? Through virtue (virtus in Latin). But not just any virtue—Aristotle’s ethics are all about the Golden Mean, the idea that virtue lies between two extremes. For example:

- Courage is the mean between recklessness and cowardice.

- Generosity is the mean between wastefulness and stinginess.

- Wit is the mean between buffoonery and boorishness.

Aristotle’s ethics aren’t about rigid rules; they’re about balance, context, and practical wisdom (phronesis-ϕρονεσισ). They’re the ethics of a person navigating the complexities of real life, not an abstract utopia.

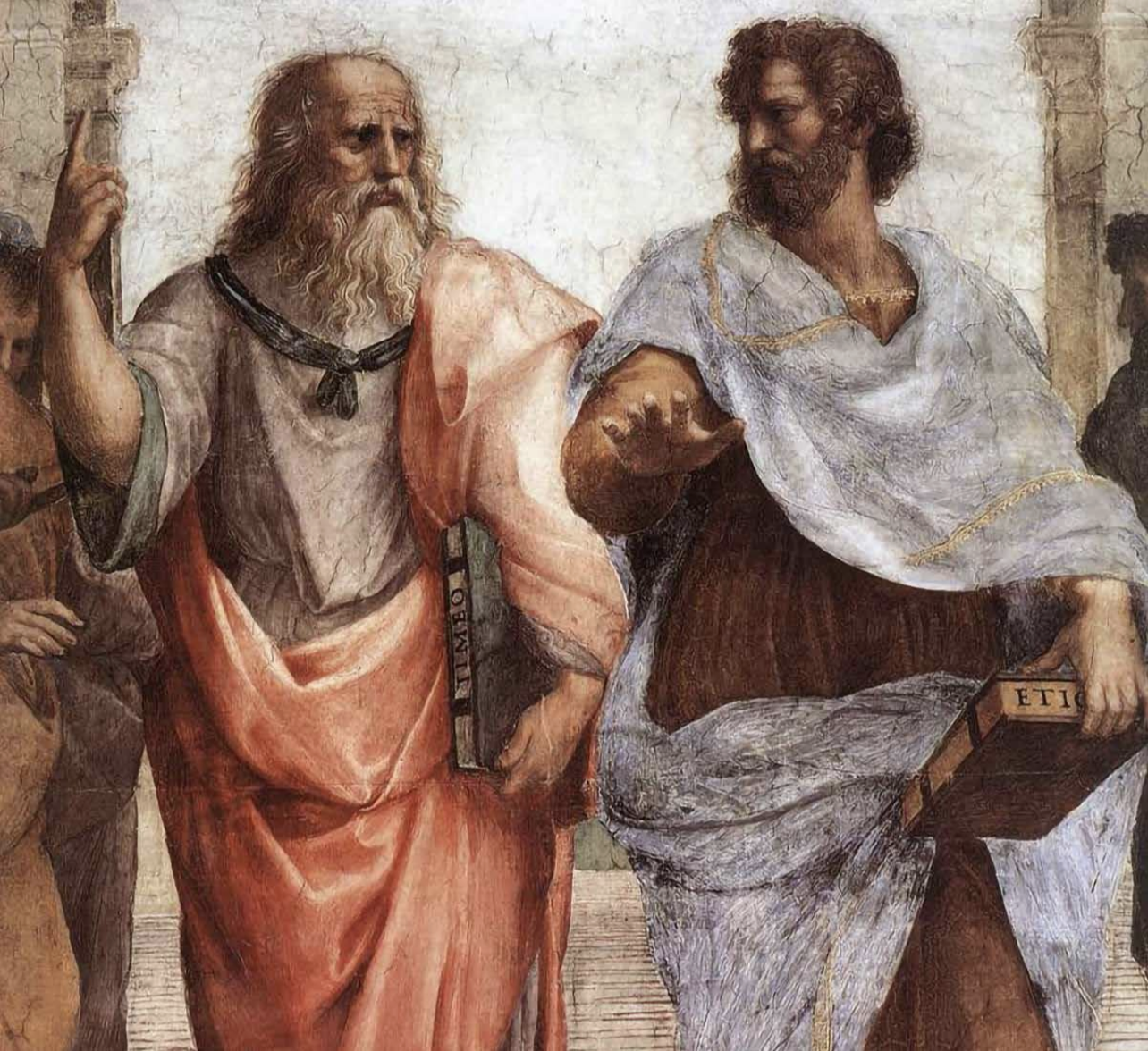

Figure 2: The hand toward the earth, indicating the materialism and rationalism of his philosophy

Aristotle’s Political Philosophy: Community as the Key to Flourishing

For Aristotle, humans are by nature political animals (ζοον πολιτικον). We thrive in communities. Why? Because it’s in the context of a community—a polis (πολισ), or city-state—that we can achieve eudaimonia. Aristotle’s vision of politics isn’t about power or control; it’s about creating the conditions for human flourishing. A good political system supports virtue and helps its citizens live good lives. It’s a vision that feels idealistic yet grounded, ambitious yet practical.

Aristotle and Science: The Father of Observation

If Aristotle were alive today, he’d probably be running a lab at Caltech. His approach to science was systematic, methodical, and deeply empirical. He didn’t just theorize—he observed, dissected, and cataloged. He studied everything from the anatomy of animals to the orbits of stars. Granted, not all of his conclusions were correct (sorry, Aristotle, but spontaneous generation is not a thing), but his methods laid the groundwork for scientific inquiry. He was the first to argue that understanding the natural world requires observation, classification, and reasoning—a methodology that still underpins modern science.

Aristotle’s Legacy: The Philosopher of the Tangible

While Plato’s influence shaped the metaphysical and abstract, Aristotle’s legacy is deeply rooted in the tangible. He’s the philosopher of the practical, the observable, the real. His ideas resonate with scientists, engineers, ethicists, and anyone who values reason and evidence.

If Plato is the dreamy theorist who inspires us to imagine what could be, Aristotle is the pragmatic thinker who helps us understand what is. Together, they form the yin and yang of Western philosophy—two sides of the same coin, each incomplete without the other.

So, as we navigate the complexities of science, research, and life, let’s remember Aristotle’s lesson: Look around, observe, question, and seek purpose. Because in the end, the pursuit of knowledge isn’t just about understanding the world—it’s about making it better.And with that, I leave you to ponder Aristotle’s wisdom. Perhaps, like him, we can find beauty and meaning not in some distant ideal but in the richness of the world around us.

And as Aristotle himself might say, We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.