What Makes Caltech Special? A Letter to Caltech’s Incoming President

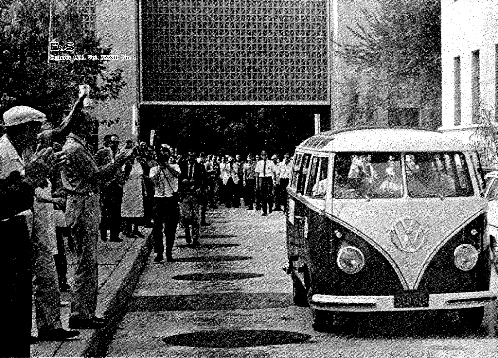

Wally Rippel (BS ‘68) and his teammates set out for Cambridge, MA (Credit: Engineering & Science)

The ‘60s were a wild time. Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, and members of the counterculture movement were defying traditional social norms. It was an age of innovation, reform, and progress, and Caltech undergraduates had their own contribution to this history: an electric car race. Take a look at the Caltech Archives and you’ll find that by 1968, Wally Rippel (BS ‘68) had modified a Volkswagen bus to an all-electric vehicle and driven it around Pasadena multiple times. Eager to test the endurance of his invention and for an opportunity to proselytize the future of electric vehicles, Rippel challenged MIT to a race in which Caltech would drive to MIT’s campus and MIT would do the reverse.

Though MIT finished first by approximately a day and a half, MIT’s Corvair had broken down multiple times and had to be towed. This led to the accumulation of penalty points on MIT’s behalf and thus Caltech’s victory. But it is not the outcome of this race but rather the scale and audacity of Rippel’s challenge that deserves attention. The infrastructure for charging the electric vehicles was provided by Electric Fuel Propulsion Company, a total of 54 charging stations across U.S. Route 66. While MIT’s car had been built by their electrical engineering department, Caltech’s had been pretty much Rippel’s own project. In 1968, the environmental effects of internal combustion engine vehicles hadn’t been on the consciousness of the general public yet; Rippel had recognized the potential for a new mode of transportation that has only begun to experience widespread adoption a half decade later.

Rippel would later go on to found AC Propulsion, a company dedicated to building induction motor based drivetrains, with fellow Caltech alumni. According to a former Chief Marketing Officer at Tesla, Martin Eberhard took a test drive in AC Propulsion’s t zero before deciding to build the Tesla roadster. While AC Propulsion never pursued the commercialization of an electric sports car and instead went back to developing compact vehicles, it was a pioneer that paved the way for future EV companies.

Stories like the Great Electric Car Race of 1968 reminds us of what makes Caltech special. It has to do with detecting gravitational waves on the sextillionth scale or beaming solar power to the earth through microwaves. It’s why Physics X, a seminar class taught by Richard Feynman, could have freshmen throw a question about an apparent violation of relativity and convince a Nobel laureate, even if just for a moment. It’s that character of being unbridled by notions of what’s possible or impossible that is at the core of the Caltech experience.

Often, that kind of free-ranging creativity is directed towards the enrichment of life outside of science. A well documented example is the Rose Bowl Hoax. In 1961, a few Techers were miffed by the fact that the Institute’s football team didn’t get as much attention as other collegiate teams at the Rose Bowl. Plotting for a way to exact justice, a group of Caltech students led by Lyn Hardy (BS ‘62) decided to tamper with the flip-card instructions for the University of Washington.

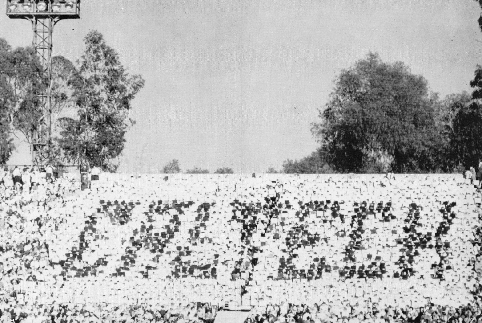

A photograph of the hoax in action (Credit: The Big T)

Here’s how it happened—as it is chronicled in the L.A. Times. Hardy, with his group of co-conspirators dubbed the “Fiendish Fourteen,” found out that the band and cheerleaders for the Washington Huskies would be staying at Long Beach State University. Accordingly, Hardy disguised himself as a high school reporter and learned how the flip-card routine would work. After the cheerleaders left for dinner, the Techers picked the lock to the cheerleaders’ room and acquired an instruction card, of which they made 2400 copies.

When the cheerleaders had again left their residence a few days later, members of the Fiendish Fourteen broke in once more. This time, they collected the master instruction sheet and modified parts of it to produce 2232 individual instruction cards. The Techers planted the cards in the cheerleaders’ room and awaited for their plan to execute on its own. The prank went fantastically well. At half time, the card displayers went through the first eleven designs as intended by its original creator. Then, aberrations started to emerge. What was supposed to be the Husky mascot looked a lot like a beaver. The word “Washington” was shown backwards. At last, the unmistakable name “CALTECH” was spelled out, for all 30 million viewers at home to behold.

Caltech is hard. And for students to succeed at the Institute, it’s crucial that the administration preserve their autonomy such that there’s enough room for decompression, for blowing off steam. Given the insatiable curiosity of Techers, that sometimes involves (metaphorically) playing with fire. Look at where those mischievous Caltech students of the past are now. There’s Carver Mead (BS ‘56), inventor of Moore’s law. There’s Kip Thorne (BS ‘62), eminent general relativity theorist and cofounder of LIGO. Likewise, there is an innumerable amount of Techers who have gone on to shape the world through science and technology. We must preserve this great lineage of thinkers, doers, and builders—and that requires an appreciation for the Caltech culture, with all its idiosyncrasies and mischief.