What I Learned From a Summer of Organic Farming

This is going to be an exercise in writing, in word vomiting, for me. i don’t have any clear idea of the scope of this piece, nor how much i’ll revise it in between typing these words and you reading them, but we have to start somewhere.

The vaguely-uniformed “random inspection" officer gatekeeping the security checkpoint at the Venice airport asked me and Sarah what we did in Europe for—how long had we been traveling?—72 days.

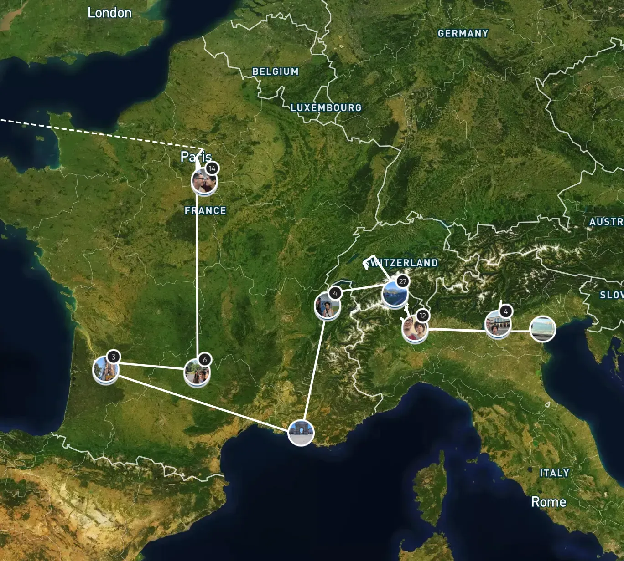

Our travels around the continent.

Living in small, rural communities and learning organic farming techniques. In between our university semesters, we said.

Hard work and juicy tomatoes at Le Petite Ferme Aufferville, a bit outside Paris

“Do you study agriculture, then?” The officer asked us with what could have been genuine interest in her voice.

“Ha, no… physics, actually.”

“Oh.” Her dark eyes squinted a little. “Then… why?”

And that’s essentially the question still bouncing around in my brain, more than a month later. To zeroth order, it was because why not. To first order, for the experience; for the chance to disconnect from the grind for a bit and live life at a slower pace. (Also, the free room and board from the World Wide Opportunities in Organic Farming program was a big draw for these broke college students.)

But what was it all for? Like, are you going to bring any of that farming stuff back with you into your daily lives?

As Sarah put it, the point of the trip was to be in the places, rather than bringing stuff back. She meant it more in the sense of physical “stuff.” But on second thought, we realized we did, in fact, bring something back with us: seeds. A literal jar of seeds, for giant sunflowers, a parting gift from our hosts Jonathan and Florence at Les Jardins de Maubert in France. Also some seed flyers from a Venice Biennale architecture exhibit — paper made from recycled fibers with actual seeds embedded. (”Plant it and you will pollinate this information,” they read.) We thought it’d be fun to grow them in the little community garden plot near the Caltech grad student apartments between Wilson and Catalina Avenue. With all the staggering amounts of food and plant waste coming out of the Institute, I reckon we can make some stuff grow with that nice, rich compost, even under the scorching southern California sun.

Quick plug for the Catalina Apartments Community Compost Pilot Program!

Is that it? came the skeptical response. Or maybe that was just the echoes of anxiety slowly decaying in the resonant cavity of my cranium. After all that immersion in permaculture, fresh air, and natural harmony… you’re just going right back to your cramped, choked, manicured, complicit metropolitan society, eyes trained on screens for a majority of your waking hours?

Yeah, alas, it’s the less-than-glamorous reality of our theoretically humankind-bettering passions for learning how the universe works and looks.

You’re just going to continue to live in housing units that source water and electricity unsustainably, as you continue to buy your food from supermarkets with questionably-responsible supply chains because it’s all you have time to shop at in between your gasoline-powered commutes and workaholic 16-plus-hour schedules of sequestering precious oxygen through your brains into arguably frivolous scientific pursuits that, from some perspectives, serve only to extract more minerals from the earth and further differentiate an elite technocratic priesthood who can afford to just move to more stable climates once the environmental effects of their industry catch up with them, leaving those with less means behind to drown?

Are your sunflowers in your little community garden enough for you?

Clearly, I brought back more than just literal seeds. My conscience been sown with metaphorical seeds of an ethos of permaculture — seeds that a foreseeable future in the city-bound academic grindset threatens to smother.

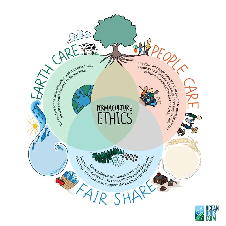

A word on permaculture — an umbrella term for various philosophies centered around nature-inspired design. After all, nature figured out the whole sustainability thing a long time ago, and it’s still a lot better at it than we are! The idea is to use natural processes to our advantage, rather than fighting against them. The practice necessitates rethinking the (many) wasteful mindsets of our culture, but in doing so, renders it far more permanent than the purportedly unshakable foundations of the life-squandering, suffering-for-profit “powers that be”.

Figure 1: The underlying concepts of permaculture (Left) and David Holmgrens’ 12 Permaculture Principles (right).

Needless to say, the ideas of permaculture (Figure 1) really resonated with our youthful anarcho-curious sensibilities throughout the summer. In particular, it was really neat to see all the different WWOOF hosts’ versions of it. Some had carved out self-sustaining niches out of practical, physical necessity; others lived out the principles voluntarily and/or selectively, in incremental effort to exist a good example; still others focused on the “fluffier” aspects of the People Care ethic, like nonviolent assertive communication. It all just makes sense — emotionally and scientifically.

So how do we keep those seeds alive? (Turns out it’s hard enough to not kill even the healthiest-looking herb plants on display at Trader Joe’s.) Do we religiously buy only organic products, even if they’re shipped from halfway around the world? Do we become hardcore environmental vegans and resign ourselves to heavily processed meat substitutes even in lieu of locally-sourced fresh flesh from happy animals? Does any individual-level action even make a difference, short of reducing our consumption to zero, growing our own food and collecting our own water and electricity? Or is our only hope of having a positive impact on the future of humanity to abandon our scientific vocations and pursue some sort of political action to turn the tides of our own self-destruction?

Even 72 days of organic farming, turning soil and harvesting plants and feeding chickens and shoveling goat manure with my own two hands, didn’t show me the answer. In fact, I think it’s a highly non-trivial—and personal—question to begin with. We could (and Sarah and I have) debate(d) the moral opportunity cost of spending time and resources on this vs. that. Save water and power on an institutional scale, vs. refuse potential interruptions to ongoing research? Raise a few thousand bucks for some environmental charity or lobby or program, vs. put it toward keeping some beloved student tradition alive? Spend a few extra seconds putting your soda can in the right bin, vs. toss it in the landfill because I heard the recycling bins here maybe don’t even get recycled? Pay a bunch of money to actually properly recycle used materials, vs. ship them to the coast of some lesser-developed country? Perhaps Camilla can weigh in with the classical thinkers’ takes for her next Philosophy Column.

My take, without getting too much into it, is that we (Caltech) can (and should) do both. We’re here, now, in this community in this location with these shortcomings and liabilities as well as those advantages and opportunities. Even though it might feel like it, reality here is no less real than at that goat farm in Italy (Figure 2). Our actions and inactions here have precisely the same global impact. (Actually, about the same acreage, too.) The difference is that at Caltech, what we do sets a strong example for other institutions with their own communities and locations, their own shortcomings and liabilities but also their own advantages and opportunities. If we wished it, we could be a world leader in not just environmental research, but also demonstration. Things to think about!

Figure 2: At a goat farm in Caprile, Italy.