Frank Capra: Caltech’s Six-time Oscar Winning Filmmaker

Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn (L) presents Frank Capra (R) with the Best Director Oscar for It Happened One Night at the 7th Academy Awards ceremony which took place on Wednesday, February 27, 1935, at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Credit: Columbia Pictures/The Kobal Collection

As the world celebrated the 97th Academy Awards this past Sunday, March 2nd, it is only fitting that we honor Caltech’s most significant contribution to the motion picture industry: six-time Oscar-winning director and former president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Frank Capra. Of his six Academy Awards, three were for Best Director, making him, outside of John Ford, tied with William Wyler and Steven Spielberg for the second-most Best Director wins, further cementing his status as one of Hollywood’s most influential filmmakers. His journey from a struggling science student at Caltech to one of Hollywood’s most celebrated directors, whose films profoundly influenced Spielberg and other current filmmakers, is a testament to the unexpected trajectories a scientific education can inspire. Over the decades, Capra’s legacy has continued to bridge the worlds of cinematic narrative, filmmaking, and science, proving that Caltech’s influence extends far beyond laboratories and equations.

In 1960, nearly four decades after graduating from Caltech, Capra, reflecting on his expansive œuvre, penned a letter to his friend, Oscar-winning director George Stevens, Jr., a filmmaker and founder of the American Film Institute. Among Stevens’ best-known films were Giant, in which he directed Elizabeth Taylor, James Dean, and Rock Hudson, as well as the critically acclaimed The Diary of Anne Frank and A Place in the Sun. The latter earned him his first Oscar for Best Director.

This rare two-page letter dated September 1, 1960, which I discovered while browsing the screenwriting archives at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library, offers remarkable insight into Capra’s lifelong commitment to Caltech and his belief that Hollywood had a role in advancing science.

While closely reading this letter, neatly typed on Capra’s company letterhead and signed by the Oscar winning director, and analyzing his writing style after partially reading a few of his scripts, I found his ability to craft compelling narratives to be genuine. His cinematic narrative was shaped not only by Hollywood conventions but also by his scientific education. Specifically, his years as a Caltech student profoundly influenced his development of logical argumentation, persuasion, and structured writing skills. Unlike many of his peers in the sciences, Capra took an unconventional academic path, enrolling in four years of English courses while pursuing his chemical engineering degree. He also contributed to The Throop Tech, the predecessor of The California Tech, where he honed journalistic clarity, structured argumentation, and persuasive writing—all of which would later appear in his films and personal correspondences.

But beyond his coursework, Capra’s scientific training instilled in him a methodical approach to storytelling. Like scientists build their arguments using evidence, hypothesis, and logical conclusions, Capra’s writing more or less follows a structured flow. This is evidenced in his passion for science, which was not just a passing interest but the fundamental principle of his early life. Before his Hollywood triumphs, he was simply a student at Throop College of Technology in 1915, having no inclination that he would one day go on to dominate the art of cinema.

Born in Bisacquino, a town and commune in the metropolitan city of Palermo in Sicily, Italy, and raised in Los Angeles, Capra pursued a degree in chemical engineering, determined to carve out a future in science. However, despite his ambition, he quickly struggled with chemistry, a subject that ultimately cost him a specialized degree. Nevertheless, he graduated in 1918 with a general science degree, a compromise that allowed him to finish his education despite failing multiple chemistry courses. Still, his time at Caltech was far from wasted. He believed scientists should not become simple thinking machines, a philosophy that would later define his filmmaking approach.

It was not just literature that captivated Capra; he was drawn to visual cinematic narrative. His interest in photography emerged when he learned the craft from Edison R. Hoge, a Caltech staff photographer at the Carnegie Institution’s Mount Wilson Observatory. Hoge introduced Capra to a newsreel cameraman, which planted the seed of his future career in motion pictures.

Thus, before Capra could consider a creative career, his life was defined by survival. Working multiple occasional jobs, he developed an intimate connection with the struggles of the working class, in which President Ronald Reagan later stated that Capra “helped all Americans recognize all that is wonderful about the American character.” These experiences later became the backbone of his cinematic themes, reflected in films like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and It’s a Wonderful Life.

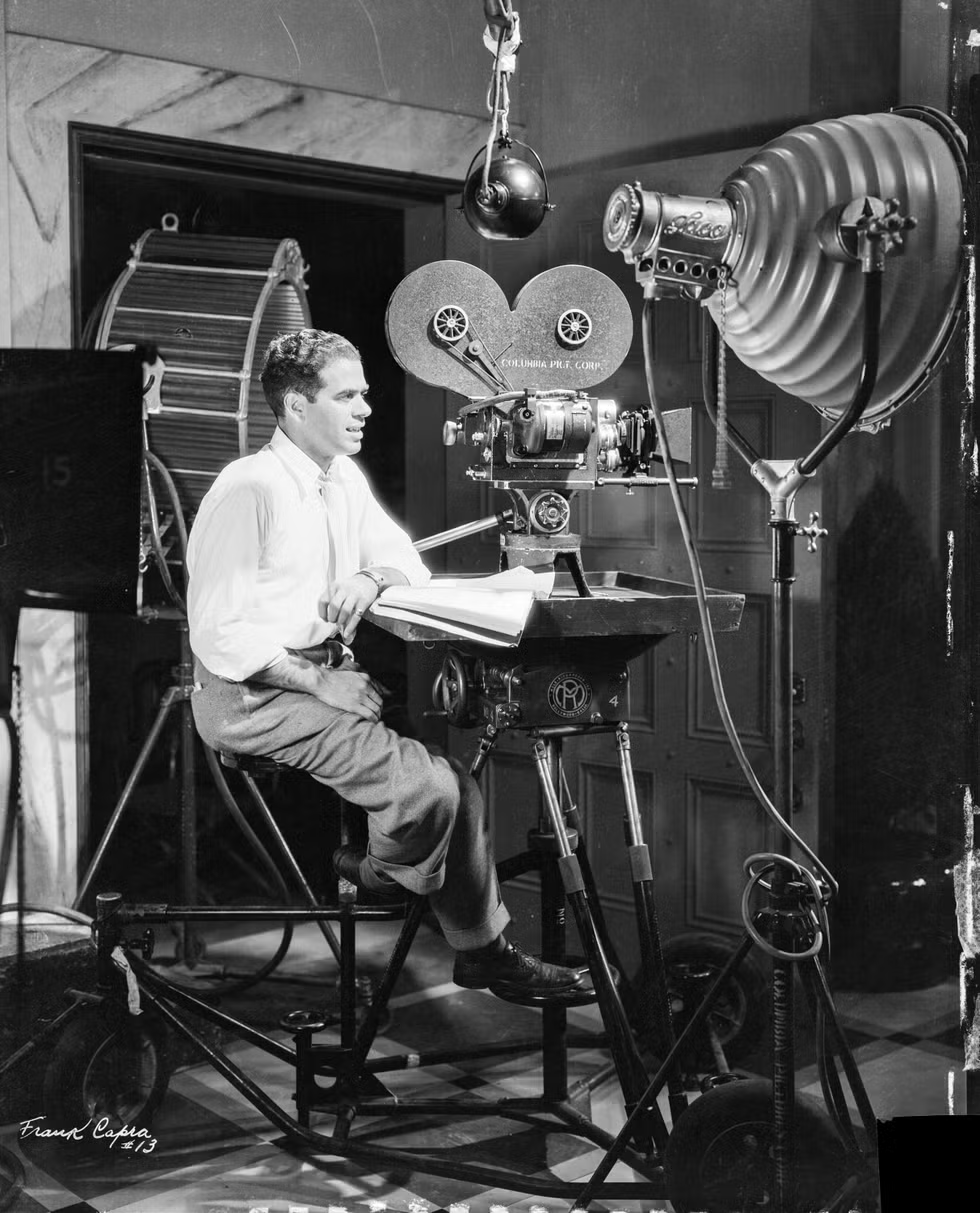

Director Frank Capra on a film set with Columbia Pictures in 1934. Credit: Columbia Pictures/ The Kobal Collection.

Capra remained dedicated to bridging the gap between Hollywood and science, ensuring that his success in film never overshadowed his commitment to scientific inquiry. And though some sources dispute this fact, his letter to Stevens, reflects his on-going passion and commitment to science and discusses the importance of scientific teaching and research. In his letter Capra directly describes Caltech’s illustrious scientists as “The cream of American scientists and researchers.”

The letter goes on to discuss Hollywood’s lack of representation in the Caltech Associates, an organization Capra was a member of, while presenting supporting evidence on the contributions of other industries to scientific progress. Capra then shares ideas on alleviating the institution’s financial pressures and ultimately proposes that Stevens join him for lunch with Caltech’s president, Dr. Lee A. DuBridge, to learn more about the solution. This structured reasoning is a hallmark of scientific writing, reflecting how Capra’s education influenced his ability to construct compelling and logical arguments.

This letter is more than just an invitation. It is a window into a different side of Capra, not the celebrated Hollywood director, but the Caltech-educated scientist who never truly left the world of academia behind. The tone of the letter is measured, analytical, and structured, reflective of a man who was as much an engineer as he was a filmmaker. Capra does not appeal to artistic sentiment or the legacy of Hollywood, as one might expect from a director writing to another. Instead, he constructs a logical case for why Hollywood should take an interest in science. Capra states, “I am writing you in the hopes that you might become interested in the greatest science center in the world: The California Institute of Technology.”

Notably, Capra’s words express a deep reverence for scientists, reflecting his unwavering identification as one of them, even decades after leaving Caltech. He writes with an analytical precision that reveals his scientific mindset rather than the typical Hollywood rhetoric one might expect from a filmmaker.

In the letter, Capra asserts that he does not need to stress the importance of scientific teaching and research—suggesting that these matters should be a categorical imperative, and should also be self-evident to any forward-thinking individual. He reminds Stevens that “right in our own backyard, scientific advancements are unfolding that will vitally affect or even change the world.” Here, Capra’s language is deeply scientific, constructed with the precision of an academic argument.

Contrarily, being a non-scientist, Stevens found this to be a difficult entry point into the conversation. Capra’s appeal is compelling, but if one is not scientifically inclined, the argument may feel inaccessible. And while the letter demonstrated a profound passion for knowledge and progress, it may have also unintentionally alienated Stevens, particularly if he felt out of his depth in a discussion about science and research.

However, Capra pivots the narrative by addressing something Stevens likely understood. He discusses 1930s Wall Street, the stock market, and its collapse, providing a historical context that grounds his argument in economic reality rather than abstract scientific ideals. He explains how certain individuals at Caltech, particularly the Nobel laureate Dr. Robert Millikan, developed a financial model to sustain the institution, collecting pledges from donors to form the Caltech Associates, which ultimately became Caltech’s most significant source of private funding.

By blending scientific reasoning with economic strategy, Capra made his argument more accessible to Stevens, who was unfamiliar with scientific discourse. Albeit not merely about securing a donation, Capra’s outreach was about constructing a bridge between Hollywood and science.

What makes this letter even more compelling is not just its content but what it reveals about Capra. This is not the Capra of red carpets and Oscar speeches, but the Capra who once spent long nights at Caltech struggling with chemical equations, who took pride in scientific progress, and who believed in the power of knowledge to shape the world. Even after Hollywood staked its claim, a part of him remained the young engineering student from Throop College, still trying to solve equations, still building bridges; not just between people, but between science and storytelling. Why he chose to approach his friend Stevens with this proposal remains uncertain; paradoxically, it suggests a belief that Stevens, with his deep Hollywood connections, could serve as an ally in fostering stronger ties between the entertainment industry and the scientific community.

Nevertheless, in his brief reply, a subsequent letter, which I also obtained a copy from the Academy archivist, Stevens, who quite literally grew up around Capra, declined the offer, stating that he would need more time before allowing himself the satisfaction of personally learning about what he described as “The Great Caltech.”

Oscar® statuettes. Credit: AMPAS/Don Emmert.

Without a doubt, Capra’s letter to Stevens proves that his commitment to Caltech and science never wavered, even at the height of his Hollywood fame. While the world remembers him for his Academy Award winning films, Capra saw himself as more than just a filmmaker. For him, it was never just about winning six 13.5-inch, 8.5-pound, bronze, 24-karat gold-plated Oscar statuettes; it was about preserving the scientific mindset that shaped his structured filmmaking artistry, and fueled his passion for discovery. His legacy continues to inspire Caltech students, demonstrating that a scientific education can open doors to unexpected yet groundbreaking careers. Through his films, whether Hollywood classics, wartime documentaries, or science productions, Capra engineered more than just stories; he shaped ideas, challenged perspectives, and left an indelible mark on generations.

Due to copyright restrictions, we are unable to publish a photocopy of the letter. However, the contents have been verified through archival sources.