An Interview with Tim Ryan

Tim Ryan enrolled in Caltech in 1973. Initially a physics major – his advisor the famous Richard Feynman – Tim soon found himself swept up by the then-hot field of electrical engineering. “We were right at the beginning of that, where the first inexpensive microprocessors had become available,” Tim recalled. Around 1975, a year before Apple released the Apple I, Tim switched to applied math. Soon, he and his roommates were using one of those new microprocessors to build an invention of their own: an all-digital music synthesizer.

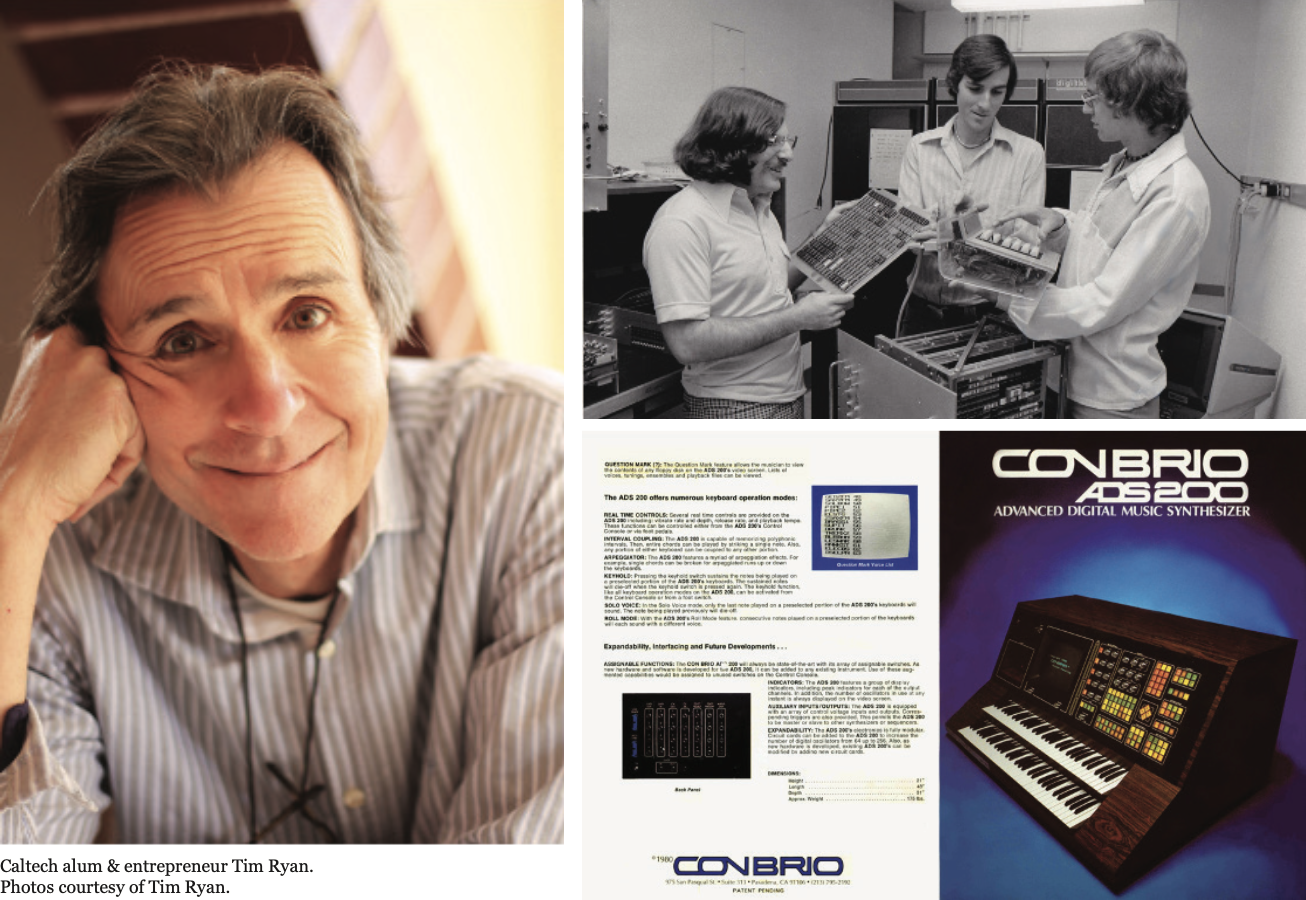

Tim teamed up with his roommates, Don Lieberman and Alan Danziger, to found Con Brio and produce the Advanced Digital Synthesizer (ADS). The ADS, a complex and expensive state-of-the-art device, saw some success. Notably, it was used for the sound effects of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) and its sequel Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982). But Con Brio only ever sold a single unit for $28,000. The experience impressed upon Tim an important lesson: however technically impressive a product, it’s profitable only if there’s a market for it.

Tim continued his entrepreneurial pursuits beyond Con Brio. After many efforts, he founded Midiman (later renamed M-Audio), which sold a variety of devices including keyboards, speakers, and audio interfaces. With M-Audio, Tim found unprecedented success. The company was eventually acquired for $174 million ($281 million in 2024). “As far as I’m concerned, M-Audio was the most successful company in the music industry when I sold it.”

A few years ago, Tim decided to return to Caltech to support undergraduate entrepreneurs. He established the Timothy D. Ryan Summer Entrepreneurship Program, a 10-week summer program which provides awardees with project funding, a stipend, and mentorship throughout the summer. The summer of 2024, Audiomatic – the dubbed translation startup Nika Chuzhoy, Brian Hu, and I co-founded – was awarded funding by the program. Tim’s early efforts with Con Brio sounded familiar to me this summer, as I worked with my two friends in our apartment, building an audio-generation tool in our era’s hot field of machine learning. We, and other aspiring undergrad entrepreneurs, have a lot to learn from his experiences.

Caltech’s honor code: how a culture of trust sparked innovation

“In 1973, [undergraduates] were given a master key that allowed us to get into every place in Caltech. Every office, every laboratory, everywhere we wanted to go we could get in. That was an attitude, as much as anything.” Tim recalled. “The steam tunnels were a big thing in our day, we could explore all of Caltech as subterranean creatures.”

It’s a vision of Caltech that is central to the school’s identity to many – and one that often feels threatened nowadays: by the rising academic honor code violations cited in the famous SAT/ACT reinstatement petition, by increasing administrative hostility towards student traditions (such as the controversial banning of Blacker’s potato cannon for rotation last year), and by tightening security around buildings – including recent installations of cameras around student residences with little advance notice to the affected students.

But it’s a vision worth fighting for, as Tim Ryan’s experience attests to. “Caltech was extraordinary in its open-door policy,” Tim reminisced. “I could go into [a cool lab] and befriend these wiser heads, and use the machine equipment… At the Caltech stores, we could buy anything we wanted to fabricate at a quarter of the cost of retail.” Tim characterized this culture as one of passively encouraging innovation, by providing readily available resources for motivated students. He summarized Caltech’s attitude as: “If you’re motivated and you know what you’re doing, go do it, we’re not stopping you.”

Undergrads today are pushing to bring back the easy access to resources and equipment that Tim Ryan enjoyed in the 70s. Luke Alvidrez (ME ‘26, Blacker) and Ethan Labelson (EE ‘26, Blacker/Dabney/Ricketts) have spent the past two years cleaning up and reorganizing the Caltech Student Shop, which will soon begin providing access to wood and metalworking equipment for students’ personal projects. Ethan and Yao Huang (EE ‘26) are also planning to establish a makerspace focused on electrical engineering. Initiatives like these promise to keep Caltech innovation thriving.

Missed and missing opportunities

Despite the extraordinary advantages that came with Caltech, the school also had its downsides. One obvious challenge was that Caltech was geared towards aspiring scientists, with, as Tim said, “woefully little resources available to help undergraduates go in a business direction.” Reflecting on his choice to fund his Summer Entrepreneurship Program, he said: “After I had fun being out in the world, enjoying the benefits of the wealth I generated, I thought, ‘What could I positively do with what I made? What would be of great benefit? At Caltech what was missing was seed money.’”

The challenges faced by Caltech entrepreneurs, however, are not just financial. Caltech’s scientific focus sometimes fosters a mindset suboptimal for smart business. “Caltech kids tend to run to their devices and solve technical problems,” Tim remarked. “They come up with brilliant solutions but at the end of the day can’t necessarily market them.” To prove his point, he described a previous team of his program’s awardees, who eventually took his advice to drop their “over-engineered, over-technical idea” — involving blockchains, I was told — for a more practical approach to their business.

Tim wishes that he had learned the importance of understanding marketing and sales earlier. “No need to spend four years developing our $28,000 machine,” he lamented. “We developed the greatest instrument the world had ever seen, but guess what? Nobody wanted it or could afford it because it was overkill.”

If he could have a do-over with Con Brio, with the business sense he learned later, he might’ve tried a radically different approach: strip the ADS down to its main board and sell it as a personal computer. “We had five 6502 microprocessors in the Con Brio. We had something far superior to the Apple II. We could have beaten the snot out of Apple, yet we were so focused on doing this immense synthesizer.”

Do you have what it takes to be an entrepreneur?

“Most people aren’t wired to take the risk – to sacrifice everything to succeed as an entrepreneur,” Tim warns. “They don’t have the ambition, the drive, or willingness to sacrifice.”

But he also boldly asserts: “If you’re smart, open-minded, and have your eyes open – in ten years, you’re going to be a multimillionaire, no matter what. You’ll find out what you need to do to succeed and do it.”

Indeed, it did take ten years between Tim’s first venture into entrepreneurship with Con Brio in 1978, and his launching of M-Audio in 1988. Each setback in that process gave him valuable knowledge. “I didn’t take a salary for almost eight years,” he said. “It was my fifth business that actually finally succeeded. Each business was more successful than the previous one.”

Tim said he’s invested in a number of companies in the past, though they’ve broadly been unsuccessful. He’s seen companies fail because of the same pitfalls Con Brio fell into. “He just kept developing more modules,” Tim said, of an investee who started with a good idea, but just couldn’t look up from the workbench long enough to sell what he was making.

Students considering entrepreneurship may think it’s likely they, too, will fail. But Tim encourages them to try anyway.

“If you don’t try it, you don’t see what you are able to do. And even if you don’t succeed, you will learn valuable tools, other than just solving tech problems, that will serve you in good stead when you go further into business. Especially if you’re going up a career path where you’re not exclusively a scientist in the lab.”

The Timothy D. Ryan Summer Entrepreneurship Program

During the interview, Tim mentioned that he hoped Caltech could develop a stronger alumni network. “There are a myriad of people at Caltech that have accomplished great things,” he said. “I wish we had a way to pull those experts out to share their experience.” In this avenue, he’s clearly trying to lead by example, dedicating wealth and knowledge he’s earned from his successful business towards supporting undergrads going through the same startup process he did.

When asked what he’s looking for in future awardees, he told me:

“We naturally ask: does this sound like an interesting thing? Does it sound viable? Would it be a good thing to bring to market? Does it sound like they can succeed at it?”

He heavily emphasized the business element. (It’s safe to say applicants would be well-advised to go beyond their technical inclinations by really knowing their market.)

“How much thought have they given to whether it’s a viable business, and have they thought of any business plan for how to sell it?” Tim added, stressing that even in an applicant’s pitch, he tries to provoke the student into thinking a little more about how they’re going to make a profit.

“My goal is to empower Caltech kids to explore the entrepreneur path, not just making something interesting and cool, but succeeding with it as a business… At the very least they will learn a whole lot. At most, something extraordinary happens.”

Applications for the Timothy D. Ryan Summer Entrepreneurship Program open at the beginning of winter term. For more information, see innovation.caltech.edu/entrepreneurship/tim-ryan-summer-entrepreneurship-program. Students interested in entrepreneurship should also check out the other programs affiliated with the Caltech Innovation Center.